Saving the Declaration of Independence

- Nick Perkins

- Aug 25, 2025

- 6 min read

The Declaration of Independence in peril

Benjamin Franklin Gates, played by Nicholas Cage, was not the first threat to the safety of the Declaration of Independence. The founding document along with the archives of American history were first endangered during the War of 1812.

On most of our tours, we describe the War of 1812 and its direct impact on Washington, DC. But we know that most visitors are unfamiliar with this conflict. August of 1814 is the pivotal month of the war for Washingtonians and here we are highlighting one of the unsung heroes of the war: Stephen Pleasanton. For more detail on the British and American movements during August 1814 and the effects on Washington DC, join us on Capitol Hill, National Archives, America Unscripted, American History, or Founders tour.

Under soft low light and the flash-free cameras of millions of visitors sit the three founding American documents: the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

Though the ink that spells the charter’s famous phrases has gone from black to a faded gray, each sheet of parchment is crammed full of stories about the origins of the country. Those tales star the Founding Fathers whose names everyone has heard: Thomas Jefferson, the Declaration’s author. George Washington, the Constitutional Convention’s president. James Madison, the Bill of Rights’ initiator. Our guides illuminate these backstories and others on our National Archives tours.

But a much harsher light almost destroyed those documents centuries ago — and none of Jefferson, Washington or Madison were responsible for saving the stories they created. Instead, if it weren’t for an early 1800s bureaucrat who has the dubious distinction of being a controversial figure among lighthouse historians, those three charters would today be ashes.

When was the War of 1812?

While writing his treatise on how to understand America, the French political philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville called the country a “great experiment.” But in 1814, the country was looking more and more like an experiment with a null hypothesis. America was in the third year of the somewhat-inaccurately-named War of 1812, essentially a second war for independence against the British.

Three years in, the British seemed to be winning. Their armies had landed in Benedict, Maryland on August 19, and began a march toward the nation’s capital in Washington, D.C. On August 22, James Monroe, the Secretary of State, was off serving as a pinch-hit war scout. He saw the British gathered just a day’s walk from Washington. To Monroe, the reason was clear: they planned to invade the District. Monroe sent word back to President James Madison and the rest of the government.

“The enemy are in full march for Washington. Have the materials prepared to destroy the bridges.” he wrote. “You had better remove the records.”

Stephen Pleasanton, the unlikely hero

The “records” Monroe referred to were the copious amount of historical documents included in the State Department’s storage facilities — the department was the main purveyor of archival materials before Franklin Roosevelt created the National Archives a century later. An entry-level clerk, Stephen Pleasonton, heard about Monroe’s dispatch, and started to scramble. His concern was minimized by other government officials who did not believe that the British could or would enter D.C. Nonetheless, Pleasanton stuffed the Declaration of Independence, Constitution and Bill of Rights into a linen bag, threw the bag onto a cart with other historically-inclusive pouches, and hoofed it out of Washington.

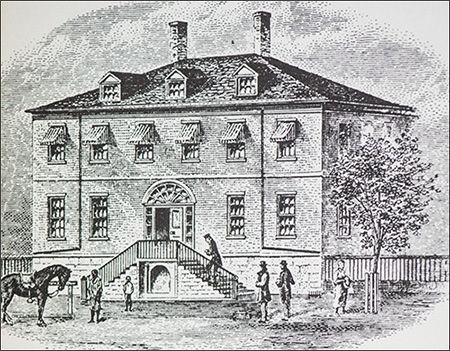

Pleasonton first brought the papers to a mill north of Georgetown, but worried that the area would be another British target because of its proximity to D.C. He gathered new wagons from the mill, and began a 40 mile journey south to Leesburg, Virginia, where he locked the documents away in a vault in the basement of the Rokeby House. The building still exists, but is privately owned.

The British come to Washington

Pleasonton’s risk-averse plan paid off. On August 24, the British burned D.C. to the ground. Their rampage included the Treasury and War Department buildings, where the documents Pleasonton saved had been held. The army torched the White House, First Lady Dolley Madison having to flee just after setting dinner. The British forces, led by Rear Admiral Sir George Cockburn, made their way to the Capitol, bursting into the House of Representatives chamber.

“Shall this harbor of Yankee democracy be burned?” Cockburn rhetorically asked his men. They replied with a resounding round of “ayes” and set about burning the small, incomplete Capitol building. This blaze consumed every page of the original Library of Congress collection and made clear what could have been the fate of our founding documents without Stephen Pleasonton.

On the morning of August 25, D.C. was in ashes, but the city was saved by the unlikeliest of forces: a tornado. Early that afternoon, a squall blew through Washington, quelling the fires and scaring the British out of town. Only a few months later, the conflict came to an official end with the Treaty of Ghent and neither side having found particular success.

The Lighthouse Service

Maybe it was fitting that a storm dovetailed with Pleasonton’s efforts because in 1820, he’d be put in charge of the Treasury Department’s Lighthouse Establishment — basically making it his job to help keep travelers safe from squalls. In these early years, the Treasury Department ran the Coast Guard and the Lighthouse Establishment as they were for the primary benefit of commercial interests which fit them under the Treasury.

Pleasonton, though, took on other responsibilities as the Fifth Auditor of the Treasury, a Department responsible for collecting revenues, managing the National Bank, constructing all federal buildings and managing the Revenue Marine (early version of the Coast Guard) and Lighthouse Service. With so many areas to manage and a thrifty nature, Pleasonton shirked his lighthouse duties and cut costs wherever possible.

Three hundred new lighthouses were added to the service during Pleasonton’s supervision, however he also returned money to the Treasury each year rather than authorizing additional spending on maintenance or other improvements. After decades of neglect, people cared enough about proper lighthouse maintenance to actually force Pleasonton’s ouster in 1852. In fact, rather than a single, stingy fist at the helm, a new board was appointed to run the lighthouses in a way that was more agreeable to coastal constituents.

“Although he was an honest man, lighthouse historians have not dealt favorably with Pleasonton. More than likely without him at the helm of our nation’s lighthouses, we would have developed into a stronger maritime nation much faster,” magazine Lighthouse Digest reflected about Pleasonton’s time in office.

But though he was at-best an uninterested lighthouse clerk, it was his guiding light in 1814 that saved those three founding documents we see today — just under lower light levels than a lighthouse would produce.

What to see in Washington DC

The founding documents are not the only national treasures that are on display from the War of 1812. Next month we will focus on the Star-Spangled Banner and its historical significance. Most visitors are unaware that there was one particular flag that inspired the writing of the national anthem and that the flag still exists. The story of this relic, on display at the Museum of American History, is one of the favorites of guides and guests alike.

On our tour of Capitol Hill, you will be able to see where the British set the Capitol alight and the first Library of Congress was lost. Then at the National Portrait Gallery you can see the portraits of the founders who once again fought for the independence of the fledgling nation against British forces. In the Museum of American History artifacts from the war bring the story to life, particularly the battles in Washington DC and nearby Baltimore. Finally, at the Archives you can see the precious documents that Pleasonton worked so hard to save. While you may not have known much about the War of 1812 before visiting Washington DC, Unscripted Tours will make sure that you have learned about the drama and heroism of this second war for independence.

Comments